Search for Excellence and Perfection

Introduction

More than a century before Galileo, one man succeeded in overcoming the age-old distinction between the contemplative and active life, between science and craft, through a unique synthesis of scientific investigation and artistic expression. For his work in which he employed physical experimentation, mathematics and reason, he has been called the first modern engineer. He anticipated many inventions which would be realised only much later, such as the airplane, the submarine, the parachute, the armoured car. But the fact that he broke entirely with the medieval Aristotelian tradition and started a new quantitative and experimental approach to a new science of matter is what makes him the forerunner of early modern scientists like Galileo, Francis Bacon, William Harvey, Nicolaus Copernicus and Isaac Newton1 .This man was Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo's lifetime was a period of great cultural turmoil, marked by such notable events as the introduction of the printing press (1455), the discovery of America (1492) and the beginning of the Protestant Reformation (1517). The Renaissance, which means a "rebirth " of ancient Greek and Roman culture, marked the decline of the Middle Ages and laid the foundations of modern times. This

1. Even though there is no direct connection between Leonardo and these early modem scientists, because none of his writings were published before 1651, there is nevertheless no doubt that Leonardo's widespread fame as an artist and engineer had a strong influence on many scientifically and philosophically oriented thinkers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Galileo Galileo (1564-1642) at least was raised in the same intellectual climate of central and northern Renaissance Italy.

Page-185

complex process of cultural evolution started in the fourteenth century with a growing dissatisfaction with the medieval concepts of man and knowledge, and brought about radical changes before it ended in the seventeenth century. A firm foundation had been laid for a new science of nature, a new materialistic and utilitarian concept of man, and a new political order of independent, secular nation-states.1 Three distinct intellectual movements contributed to that process: the humanists, the Aristotelian scholars, and the artists and craftsmen.

The humanists were originally university teachers of rhetoric, grammar, poetry and history, but came to include educated laymen, civil servants and merchants. To the humanists, the ideal individual was one equipped with intellectual and practical skills, and viewed as the conscious mover of his own fate. To them, the aim of life was success and fulfilment in the world, not beyond it. This new image of man as an active individual striving rationally towards worldly success began to replace the medieval world-view which was centered around religion and conceived of man s earthly existence as a mere preparation and test for the promised life after death.

Simultaneously, the Aristotelian scholars who constituted the scientific community during the Middle Ages began a critical reflection on their traditional approach to science. Aristotelian science was based on daily-life experience and common sense and operated in a closed world the earth as its centre about which everything to be known had already been expounded by the great philosopher himself. This approach was naturally inimical to discovery and innovation, for it could not provide a conceptual framework within which new knowledge could be generated. This was especially crucial in the natural sciences like biology and physics where newly gathered information only too often proved Aristotle wrong. At first this situation led to a sort of scientific pluralism in the explanation of nature, and magic, alchemy and astrology flourished; but in the end, the new sciences of biology and physics based on reason, experiment and mathematics replaced the old Aristotelian concept of human knowledge.

The third movement contributing to the cultural change from the Middle Ages to modern times involved the Renaissance artists and craftsmen who were originally

1. The first scientific academy, the Academla Secretorum Naturae, was founded in Italy by the natural philosopher Giambattista della Porta in 1560. The final institutionalisation of modem science is generally attributed to the foundation of the Royal Society in England in 1662, and to the Academic des Sciences in France in 1669.The modem image of man originated in Renaissance philosophy and particular influence can be found in the works of humanists like Petrarch (De Remedius Utriusque Fortunae, 1366), Leon Battista Albert! (Della Famiglia, On the Family 1444), and Pico della Mirandola (De Dignitate Hominis, On the Dignity of Man 1486). The final dominance of this utilitarian image of man oriented around worldly success can be found in Adam Smith's An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776. The secular nation-states of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in France, England and Spain replaced Papal and feudal power.

Page-186

manual workers like painters (white-washers), masons and blacksmiths. Usually they lacked any formal education and had to rely exclusively on the knowledge transmitted orally through their guilds, and on their own experience and skill. Engaged in solving practical problems of construction and decor, they began to apply mathematics and experimentation as indispensable tools for their work. They found that the artist's freedom to create was limited by nature s own rules, and hence saw that a thorough knowledge of the hidden structure of reality was a necessary condition for any artificial recreation by the artist.

Leonardo da Vinci belonged to this third group. He received only a very basic formal education and was thirty years old when he finally learned Latin, a necessary tool since most books of these days were written in Latin. Yet his broad interest in scientific matters makes him an outstanding exception among the craftsmen and painters of his time. Leonardo transcended all traditional boundaries between science and art, and in the process raised both fields to new heights.

Page-187

Virgin of the Rocks, by Leonardo da Vinci

Page-188

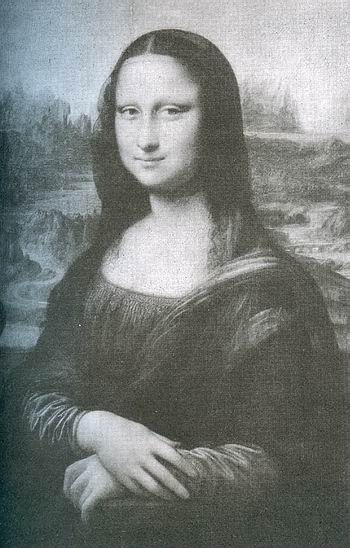

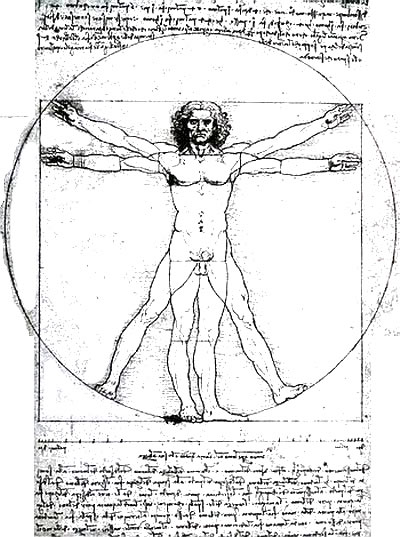

The man who painted the world-famous Mona Lisa was born near the village of Vinci, in the countryside of Florence, on April 15, 1452. He was baptized Leonardo and was to become one of the most brilliant figures in a fascinating period of European history, the Italian Renaissance. He is mostly known as an artist, but he was much .more, and his impact on the course of Western history has been immeasurable. Leonardo's unparalleled diversity of talents justifies calling him a "genius", a true embodiment of the Renaissance ideal of a universal man. Not only did he excel as a painter and sculptor, but he displayed a whole range of artistic and scientific capacities in such diverse fields as mathematics, mechanics, aeronautics, anatomy, geography, botany, astronomy, military engineering and even town planning and architecture.

Leonardo began his career as a painter in his hometown, Florence, which was one of the two cultural centres of Renaissance Italy, the other being Venice. He became an apprentice to the painter and sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio, who is reported to have stopped painting when he saw that his young student Leonardo had surpassed him." Leonardo enjoyed inspiring companionship: among his fellow- students were Ghirlandaio and Perugino. And in the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo di Medici, "Il Magnifico", Leonardo found an art-loving patron who generously promoted all the arts, literature and philosophy.2 But after executing a few major works the large panel painting The Adoration of the Magi3 is a revealing example of his early mastery and remarkable talent Leonardo left his hometown in 1482 to work for Ludovico Sforza, "II Moro", duke of Milan.4 The motives for this decision are not completely clear, but it seems that the intellectual atmosphere of Florence, which at that time was strongly influenced by mystical Hermetism and esoteric Neoplatonism, did not appeal to the more rationally inclined Leonardo.5 He was an independent and critical investigator who despised dogma as well as magic as futile attempts to understand and influence reality. Alchemy to him was nothing more than "the most foolish opinions", and he even expressed his hope that the flourishing astrologers of his day would be castrated.6 He showed the same attitude towards Christian doctrine, if one can trust his sixteenth century biographer Vasari who related that "Leonardo was of so heretical a cast of mind that he conformed to no religion whatever, accounting it perchance much better to be a philosopher than a Christian."7

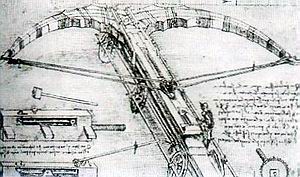

At any rate, when Leonardo heard that Ludovico wanted a military engineer, an architect, a sculptor, and a painter, he decided to offer himself as all these in one. And so he wrote his famous letter:

Page-189

Most Illustrious Lord, having now sufficiently seen and considered the proofs of all these who count themselves masters and inventors of instruments of war, and finding that their invention and use of the said instruments does not differ in any respect from those in common practice, I am emboldened without prejudice to anyone else to put myself in communication with your Excellency, in order to acquaint you with my secrets, thereafter offering myself at your pleasure effectually to demonstrate at any convenient time all those matters which are in part briefly recorded below.

I have plans for bridges, very light and strong, suitable for carrying very easily...

When a place is besieged I know how to cut off water from the trenches, and how to construct an infinite number of... scaling ladders and other instruments ...

I have plans for making cannon, very convenient and easy of transport, with which to hurl small stones in the manner almost of hail...

And if it should happen that the engagement is at sea, I have plans for constructing many engines most suitable for attack or defense, and ships which can resist the fire of all the heaviest cannon, and powder and smoke.

Also I have ways of arriving at a certain fixed spot by caverns and secret winding passages, made without any noise even though it may be necessary to pass underneath trenches or a river.

Also I can make covered cars, safe and unassailable, which will enter the serried ranks of the enemy with artillery, and there is no company of men at arms so great as not to be broken by it. And behind these the infantry will be able to follow quite unharmed and without any opposition.

Also, if need shall arise, I can make cannon, mortars, and light ordance, of very beautiful useful shapes, quite different from those in common use.

Where it is not possible to employ cannon, I can supply catapults, mangonels, traps, and other engines of wonderful efficacy not in general use. In short, as the variety of circumstances shall necessitate, I can supply an infinite number of different engines of attack and defense.

In time of peace I believe that I can give you as complete satisfaction as anyone else in architecture, in the construction of buildings both public and private, and in conducting water from one place to another.

Also I can execute sculpture in marble, bronze, or clay, and also painting, in which my work will stand comparison with that of anyone else whoever he may be.

Moreover, I would undertake the work of the bronze which shall endue with immortal glory and eternal honour the auspicious memory of the Prince your father and of the illustrious house of Sforza.

And if any of the aforesaid things should seem impossible or impracticable to anyone, I offer myself as ready to make trial of them in your park or in whatever place shall please your Excellency, to whom I commend myself with all possible humility.8

Page-190

|

|

|

It is not known what Ludovico replied, but the thirty-year-old Leonardo entered the splendid court of Ludovico Sforza with great acclaim. He was described as "a beautiful person, well proportioned, with a fine beard well arranged in ringlets, reaching down to the middle of his chest",9 and he fascinated his audience with his playing on a lyre his own hands had fashioned in the form of a horse's head, with

Page-191

Study for the head of Judas in view of the depiction of the Last Supper

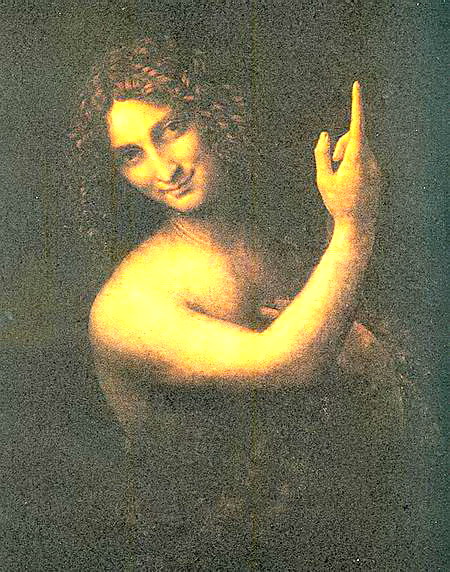

his gentle voice, and with his subtle arguments in conversation. "His powers of conversation were such as to draw to himself the souls of listeners", remembers Vasari.10 Employed as a "painter and engineer of the Duke", Leonardo directed an extensive workshop with several students, entertained the court with his decorations for the frequent festivities, and did some paintings, among them the beautiful Virgin of the Rocks and the monumental Last Supper.

The story of the execution of this last painting gives telling insights into the personality of the great painter. Shortly after he entered Ludovico's service, the Duke asked him to depict the Last Supper on the far wall of the refectory where the Dominican friars took their meals, at the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. For three years (1495-98) Leonardo laboured but dallied at the task. The head of the monastery complained to Ludovico of Leonardo's apparent sloth: the painter would sit before the wall for hours without painting a stroke. Leonardo explained to his patron that the artist's most important work lies in conception rather than execution.

Page-192

In this case he had two great difficulties, he said: to conceive features worthy of Jesus Christ, and to picture a man as heartless as Judas. Leonardo spent much of his time searching the streets of Milan for heads and faces that could serve him in representing the Apostles. One of the tragedies of Leonardo's life is that because of certain unconventional mural techniques the paint soon began to flake and fall. Leonardo shunned the traditional fresco method where the painter had to work fast on wet plaster, and tried a new mixture of colours intended to give the painter more time for contemplation. Today, although we can hardly study the shades of subtleties of the painting, the composition and general outlines alone make it evident that The Last Supper deserves to be called the greatest painting of the Renaissance.

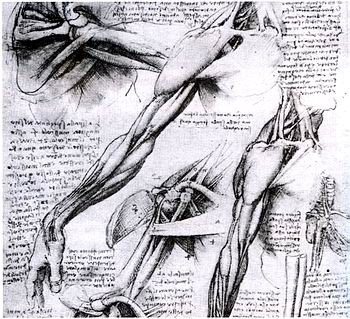

Leonardo's most ambitious project for Ludovico, a sixteen-feet high equestrian statue in honour of Francesco Sforza, the Duke's father, was a failure, an exhausting and unnerving experience for Leonardo. The tons of bronze intended for the statue were instead used to make cannonballs to fight the French who were then menacing Milan. After four years of work, Leonardo had only finished the clay model of the horse, which the French soldiers used as a target when they captured the city. The many anatomical sketches Leonardo had made were of such excellent quality that they set a new standard for anatomical drawings.

During the seventeen years Leonardo stayed in Milan he released the creative power of his investigative mind through the study of nature by all sorts of different means; ranging from geometry, architecture and painting to geology, biology and mechanical engineering. He recorded the proceedings of these studies in notebooks, writing the Italian vernacular in a strange mirror-script." He is said to have composed about 120 manuscripts, and the fifty that remain are a treasure for historians of science and philosophy. He combined text and illustrations as a method he called it dimonstratione (demonstration) to present his discoveries and inventions; but the notebooks were never published.

One of the most striking themes in the notebooks, one which Leonardo spent half his life studying, is the problem of human flight. He envied the birds as a species in some ways superior to man. He studied every aspect of their wings and tails, and the mechanics of their soaring, gliding, turning and descending. And he planned the conquest of the air:

You will make an anatomy of the wings of a bird, together with the muscles of the breast, which move these wings. And you will do the same for a man, in order to show the possibility of a man sustaining himself in the air by the beating of wings.12

Page-193

A bird is an instrument working according to mechanical law. This instrument it is within the power of man to reproduce with all its movements, but not with a corresponding degree of strength."

In a brief essay, Sul Volo (On Flight), he described a flying machine made by him of strong cloth, leather and silk. He called this machine "the bird" and wrote instructions on how to fly it:

|

|

|

Studies for a flying screw or helicopter (top left), for a parachute (top right) and for a flying machine (bottom).

Page-194

Make trial of the Machine over the water, so that if you fall you do not do yourself any harm ..14.

The great bird will take its first flight... filling the whole world with amazement and all records with its fame; and it will bring eternal glory to the nest where it was bom.15

During Leonardo's lifetime only one work of his was published, a collaboration with the mathematician Luca Pacioli, entitled De Divina Proportione (on Divine Proportion), published in Venice in 1509. His Treatise on Painting was edited after his death by his lifelong friend Francesco Melzi.16 This work must be seen in the context of the ongoing Renaissance discussion on the scientific foundation of art, as exemplified by the works of L .B. Alberti and Piero della Francesca.17 In the Treatise, Leonardo demonstrated the mathematical and biological basis of the art of painting, described the geometry of space and functioning of the eye, and expounded the concept of saper vedere (to know how to see), as the creative method not only for painting but for every conscious artistic expression. For Leonardo, "the eye is the window of the soul"18 and the most noble of the senses, constantly reflecting and determining what we call "reality". The painter once endowed with the powers of perception and the perfect ability to pictorialize what he perceives becomes thus a real scientist, achieving knowledge by observation and reproducing that knowledge authentically.

Unexplained gaps in the chronology of Leonardo's life between 1482 and 1487 have given rise to speculations about a journey to the Near East or even Asia, but apart from some passages in the Codice Atlantico notebook, there is no convincing evidence. In 1499 the French King Louis VII captured Milan and soon afterwards Leonardo and his friends returned to Florence where he was welcomed with honour and given ample opportunity to work. He made the cartoon for an altarpiece, The Virgin, Child, and St. Anne, and when it was publicly displayed it attracted large crowds of people who came as if attending a solemn festival. But his life was "so irregular and unsettled that he may be said to [have lived] from day to day."19 Only his constant search for new frontiers can explain his decision to enter the service of the ruthless commander-in-chief of the Papal Army, Cesare Borgia, son of the notorious Pope Alexander VI.20 Borgia was entrusted with the mission of gaining control of central Italy, and Leonardo stayed with him as his "military engineer" for almost one year. Besides military advice, he supplied maps of cities and topographical sketches which laid the foundation of modem cartography.

Page-195

Upon his return to Florence the governing council of the city organised a competition in the Palazzo Vecchio for the best mural painting on an historical theme. The population of Florence watched in expectation as the two greatest artists of the day, Leonardo and Michaelangelo, became competitors. But neither Leonardo's Battle of Anghieri nor Michaelangelo's Battle of Cesna were completed. It is not clear whether Leonardo's return to Milan in 1506 was precipitated by personal quarrels with Michaelangelo or by disappointment with another failure to employ a new technique for the monumental (7 meters by 17 meters) mural (he seems not to have learned the lesson of The Last Supper). However he asked for and was granted permission to leave Florence and work in Milan for the French Chancellor, Charles d'Amboise. Here Leonardo stayed for six years, decorating palaces, preparing festivals, designing canals and sewage systems for Milan, studying anatomy, and doing some painting. But his success as an engineer and scientist was marred by

Anatomical studies

Page-196

another disappointment in his work as a sculptor, when again an equestrian monument this time for a victorious French Marshal did not go beyond the stage of preliminary sketches. At any rate, it seems that Leonardo was more and more occupied with the scientific investigation of matter, and his notebooks of that time, including mechanical, optical, mathematical, biological and geological studies, reveal that he was increasingly convinced that nature worked on the basis of mathematically explicable rules. "Let no man who is not a mathematician read the elements of my work,"21 he insisted, recalling the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid and anticipating the quantification of natural philosophy by Galileo.

When the French lost Milan in 1513, Leonardo, now sixty, again had to move. He left for Rome where the art-loving Pope Leo X (formerly Giovani di Medici) commissioned great works from Raphael, Michaelangelo, Bramante and Peruzzi.22 He was entertained at the Belvedere, a summer palace atop the Vatican Hill, but

|

Mona Lisa |

Virgin, Child and St. Ann |

Page-197

could not find the place he deserved as a master artist and received no large commission from the Pope. In fact, Leo X complained about him: "This man will never get anything done, for he is thinking about the end before he begins."23 Thus, after three years of disappointment and loneliness in Rome, Leonardo readily accepted an invitation from King Francis I to come to France. He spent the last three years of his life, accompanied by the faithful Francesco Meizi, in the castle of Cloux near the Loire river, greatly admired by the French King who later told Benevenuto Cellini that he "believed no other man had been born who knew as much about sculpture, painting and architecture, but still more... was a very great philosopher."24 Francis I left Leonardo complete freedom to make finishing touches on some of his paintings and to rearrange and edit his notebooks. Leonardo died on May 2, 1519, and was buried in the palace Church of Saint Florine, which was destroyed during the French Revolution and completely torn down in the early nineteenth century. Except for his creations, no trace of Leonardo remains. But he once wrote: "A day well spent makes it sweet to sleep, so a life well used makes it sweet to die."25

Four centuries later, we may be able to see Leonardo's impact and significance on the course of history much more clearly than his contemporaries, among whom only a handful realised his unique talent and his advanced state of consciousness. His synthesis of science and art, of investigation and expression, was a major break- through on the way towards modern empirical and rational science. His paintings, above all Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, are such extraordinary renderings of physical and spiritual realities as to be considered immortal peaks of art. In sculpture he conceived the greatest projects of his age, and the anatomical sketches for the two equestrian monuments still rank among the best works ever done in anatomy. As a scientist, besides inventing many curious devices, he initiated a new way of exploring matter: his methods of experiment and quantification combined with visual demonstrations and textual explanations anticipate the modern scientific methods, and his concept of "force" as the prime agent in organic and inorganic matter has become a fundamental notion of modern physics. His science of seeing, saper vedere, as a precise method of revealing and understanding the secrets of reality ranks beside Socrates' Know that you do not know as a philosophical and practical guideline for a conscious life.

The philosopher and historian Will Durant has this to say about Leonardo:

How shall we rank him? though which of us commands the variety of knowledge and skills required to judge so multiple a Man? The fascination of his polymorphous

Page-198

mind lures us into exaggerating his actual achievement; for he was more fertile in conception than in execution ... And yet Leonardo's studies of the horse were probably the best work done in anatomy of that age; Ludovico and Cesare Borgia chose him, from all Italy, as their engineer; nothing in the paintings of Raphael or Titian or Michaelangelo equals The Last Supper; no painter has matched Leonardo in subtlety of nuance, or in the delicate portrayal of feeling and thought and pensive tenderness; no statue of the time was so highly rated as Leonardo's plaster Sforza; no drawing has ever surpassed The Virgin, Child and Ste Anne; and nothing in Renaissance philosophy soared above Leonardo's conception of natural law. He was not "the man of the Renaissance", for he was too gentle, introverted, and refined to typify an age so violent and powerful in action and speech. He was not quite "the universal man", since the qualities of statesman or administrator found no place in his variety. But, with all his limitations and incompletions, he was the fullest man of the Renaissance, perhaps of all time. Contemplating his achievement we marvel at the distance that man has come from his origins, and renew our faith in the possibilities of mankind.26

Leonardo's constant search for precision in cognition and for perfection in expression often brought him beyond the scope of the original task at hand, and he sometimes got lost in experimenting with details and distracted by exploring new possibilities. Sometimes when his thirst for knowledge was satisfied he lost interest in his subject and would drop it in favour of new frontiers. And only too often the ignorance and arrogance of his patrons frustrated him. His spiritual aspirations to see and to express clashed with the imperfections of the physical world. There was in him some conflict between the spiritual and the material. But in the instances that Leonardo was able to overcome this seeming contradiction and synthesize his vast talents, the results were so stupendous that they remain timeless inspirations in the search for an integral aim of life.

Page-199

Auto-Portrait of Leonardo in old age

1. Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-1488) was and outstanding and widely talented artist. He directed the most important workshop in Florence during Leonardo's youth. His most famous work is the bronze statue David, in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence.

2. The Medici were a family of bankers and traders who ruled Florence and later Tuscany from 1434 to 1737. They provided three Popes, married into the royal families of Europe and were exceptional patrons of art. Lorenzo (1449- 1492) continued the tradition of his father Cosimo and surrounded himself with philosophers, poets and artists.

3. The Adoration of the Magi is a popular theme of Christian mythology. Leonardo's painting should be seen in contrast with those of Sandro Botticelli (1475) and of Albrech Durer (1483).

4. Ludovico Sforza (1452-1505), an offspring of the Milanese Sforza dynasty, made Milan the most splendid court in Europe during his reign.

5. Renaissance Neoplatonism was a philosophical movement that returned to the ancient sources of Platonic philosophy. Sponsored by the Medici, the Platonic Academy of Florence became the leading centre for the study and translation of Platonic texts. Masilio Ficino (1433-1499) and Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) were its major philosophical exponents, while Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) visualised the Platonic world-view in his painting Primavera (Spring) in 1475. See Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance (London: Faber and Faber, 1958).

Hermetic literature dates from the first to the last parts of the third century AD, and was rediscovered during the Renaissance. Hermetism is an effort to bridge the gap between religion and science and to deify man through knowledge of the world and experience of the transcendent divinity.

6. Cf. Will Durant, The Story of Civilization Part V: The Renaissance. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1953), p. 222.

7. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) was an artist and, more importantly, an art historian whose book Le Vito dei piii eccelenti Architetti, Pittori, e Scultori Italian!, published in 1550, gives a detailed account of the life of Leonardo. Vasari is quoted from Irma A. Richter, The Notebooks of Leonardo da vinc, (Oxford University press, reprint 1980), p.288.

Page-200

8. Reproduced by Will Durant, op. cit., pp. 202-203.

9. Richter, op. cit, p. 293.

10. Vasari, quoted in Richter, op. cit., p. 330.

11. For recent editions of Leonardo's notebooks, see Jean P. Richter, T1ie Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, 3rd ed., 2 vols. 1970; or Edward McCurdy, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci,! \o\s., 1955.

12. Leonardo, Codice Atlantico; quoted by Will Durant, op. cit., p. 220.

13. Leonardo, Codice Atlantico; quoted by Will Durant, op. cit., p. 220.

14. Cf. Irma A. Richter, op. cit. p. 298.

15. Leonardo, Sul Volo, quoted by Will Durant, op. cit., p. 220.

16. Luca Pacioli (1450-1520) an eminent Renaissance mathematician, published De Divina Proportione in Venice in 1509. Two recent editions of the Treatise on Painting by Leonardo are: C. Pedretti, On Painting: A Lost Book, (Berkeley, 1964); and A. 0. MacMahon, Treatise on Painting, (Princeton, 1956).

17. Geometrical perspective as a tool to pictorialise space was discovered during the Renaissance by several artists. The first publications on that theme are from Piero della Francesca (1420-1492), one of the most important artists of the Renaissance, in De Prospettiva Pingendi, 1482; and Delia Pittura by Leon Battista Alberti.

18. Leonardo, Trattato della Pittura; cf. IrmaA. Richter, op. cit., p. 4.

19. Vasari as quoted by Irma A. Richter, op. cit., p. 341f.

20. The Spanish Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia (1431-1503) became Pope Alexander VI in 1492. Indulging in orgies and crime he is often regarded as the personification of the declining moral standards of the Vatican during the Renaissance. His son Cesare (1475-1507) and his daughter Lucrezia (1480-1519) were of the same mould, unscrupulously pursuing power and wealth. For Niccolo Macchiavelli, Cesare Borgia was a model of the successful secular ruler. See Niccolo Macchiavelli, II Principe, (The Prince).

21. Cf. Will Durant, op. cit., p. 222.

22. Giovani di Medici acquired Papal authority in 1503 and tried to consolidate the Vatican after the devastating rulership of Pope Alexander VI. Bramante (1444-1514), the architect of St. Peter's Bassilica, Michaelangelo (1475-1564) the sculptor, and Raphael (1483-1520) the painter were among the artists who found generous employment in Rome during his reign.

23. Vasari, as quoted by Richter, op. cit., p. 377.

24. Benevenuto Cellini, quoted by Richter, op. cit., p. 383.

25. Will Durant, op. cit., p. 227.

26. ibid, pp. 227-28.

Page-201

Extracts from Leonardo's Notebooks:

Reflections on Life

We are deceived by promises and deluded by time, and death derides our cares; life's anxieties are nought.

That man is extremely foolish who always is in want for fear of wanting; and his life flies away while he is still hoping to enjoy the good things which he has acquired with great labour.

He who possesses most is most afraid to lose.

0 time, consumer of all things! 0 envious age, thou destroyest all things and devourest all things with the hard teeth of the years little by little, in slow death. Helen, when she looked in her mirror and saw the withered wrinkles which old age had made in her face

Page-202

wept and wondered why she had twice been carried away. 0 Time, consumer of all things! 0 envious age, whereby all things are consumed!

...The miserable life should not pass without leaving some memory of ourselves in the minds of mortals.

... Lead: Leather a weight of lead pressing forwards and backwards a little bag of leather filled with air, the descent will show you the hour. We do not lack ways and means to divide and measure these miserable days of ours which it should be our pleasure not to spend and pass away in vain and without praise, and without leaving record of themselves in the minds of men; so that this our miserable course should not be sped in vain.

0 thou that sleepest, what is sleep? Sleep resembles death. Oh, why not let thy work be such that after death thou mayst retain a resemblance to perfect life, rather than during life make thyself resemble the hapless dead by sleeping.

Shun those studies in which the work that results dies with the worker.

I obey thee, Lord, first for the love which I ought reasonably to bear thee; secondly, because thou canst shorten or prolong the lives of men.

In rivers, the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes: so with time present. Life if well spent is long. The age as it flies glides secretly and deceives one and another; nothing is more fleeting than the years, but he who sows virtue reaps honour.

In youth acquire that which may restore the damage of old age; and if you are mindful that old age had wisdom for its food, you will so exert yourself in youth, that your old age will not lack sustenance.

While I thought that I was learning how to live, I have been learning how to die.

To the ambitious, whom neither the boon of life, nor the beauty of the world suffice to content, it comes as penance that life with them is squandered, and that they possess neither the benefits nor the beauty of the world.

As a day well spent brings happy sleep, so a life well used brings happy death.

Every evil leaves a sorrow in the memory, except the supreme evil, death, which

Page-202

destroys this memory together with life

.

Wrongfully do men lament the flight of time, accusing it of being too swift, and not perceiving that its period is sufficient. But good memory wherewith nature has endowed us causes everything long past to seem present.

Our judgement does not reckon in their exact and proper order things which have come to pass at different periods of time; for many things which happened many years ago will seem nearly related to the present, and many things that are recent will seem ancient, extending back to the far-off period of our youth. And so it is with the eye, with regard to distant things, which when illumined by the sun seem near to the eye, while many things which are near seem far off.

[With a drawing of two figures, one pursuing the other with bow and arrow} A body may sooner be without its shadow than virtue without envy.

When Fortune comes, seize her in front with a sure hand, because behind she is bald.

Just as iron rusts from disuse, and stagnant water putrefies, or when cold turns to ice, so our intellect wastes unless it is kept in use.

[With a drawing of butterflies fluttering round aflame}

Blind ignorance misleads us thus and delights with the results of lascivous joys.

Because it does not know the true light.

Because it does not know what the true light is.

Vain splendour takes from us the power of being ...

Behold how owing to the glare of the fire we walk where blind ignorance leads us.

0 wretched mortal, open your eyes!

[With drawings of compass and plough]

He turns not back who is bound to a star.

Obstacles do not bend me.

Every obstacle yields to stem resolve.

Good culture is born of a good disposition; and since the cause is more to be praised than the effect, you will rather praise a good disposition without culture, than good culture without the disposition.

Where there is most feeling there is the greatest martyrdom.

Page-204

Page-205

The highest happiness becomes the cause of unhappiness, and the fullness of wisdom the cause of folly.

The part always has a tendency to unite with its whole in order to escape from its imperfection.

The soul's desire is to remain with its body, because without the organic instruments of that body it can neither act nor feel.

The soul can never be corrupted with the corruption of the body, but acts in the body like the wind which causes the sound of the organ, where if a pipe is spoiled, the wind would cease to produce a good result.

Whoever would see how the soul dwells within its body let him observe how this body uses its daily habitation, for if this is without order and confused the body will be kept in disorder and confusion by its soul.

Extracts selected and edited by Inna A. Richter, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci,

Oxford University Press, reprint 1980, pp. 260-61 and pp. 273-275.

A few dates

|

1452(April) |

- Birth of Leonardo. |

|

1469 |

- Leonardo's family moves to Florence. |

|

1481 |

-Adoration of the Magi. |

|

1482 |

- Leonardo goes to Milan and works for Ludovico, Regent of Milan. |

|

1483 |

- The Virgin of the Rocks. |

|

1500-1 |

- Leonardo goes back to Florence. |

|

1502(June) |

- Military engineer to Caesar Borgia in Romagna. |

|

1503(April) |

- Back to Florence. |

|

1503-6 |

- Painting of Mona Lisa. |

|

1507 |

- Leonardo is appointed as "painter and engineer in ordinary" to the King of France in Milan. |

|

1513 |

- Rome: Leonardo works for the Pope Leo X. He is more and more attracted by Science. |

|

1516 |

- Leonardo goes to France, invited by the King Francis 1st and settles in Cloux, near Amboise. |

|

1519(May2) |

- Death of Leonardo. |

Page-206

Suggestions for further reading

Burckhardt, Jacob. The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. London: 1914.

Clark, Kenneth. Leonardo da Vinci. Penguin Books.

Durant,Will. The Story of Civilization'. Part V. The Renaissance. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1953.

The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Selected and edited by Irma A. Richter, Oxford University

Press, World's Classics Edn., 1980.

Richter, Jean Paul. Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci. Oxford University Press, 2nd edn., 1939.

Page-207